Segregation and urban spatial structure in Barcelona

The coexistence in Barcelona between inhabitants of different ethnic groups generates segregation by difference of income; not for ethnic reasons. This is evidenced by the analysis of the urban spatial structure of the city carried out by researchers from the department of Applied Economics of the UAB. The study has determined, on the one hand, the displacement of low-income groups to poor neighborhoods, deprived of a residence in places of interest due to gentrification and, on the other hand, education as a hopeful way to introduce this sector to the space "banned" for economic reasons.

One of the distinguishing features of Barcelona is its attractiveness as a destination for migrants. Evidence from the 20th century attests to that appeal, especially the total number of internal migrants who settled there in the 1950s and 1960s during the first waves of migration. Later, in the 2000s, significant international migration stimulated inflows of migrants that ultimately accounted for approximately 20% of Barcelona’s population. The experiences of US and even other European cities reveal that multiethnic cities often suffer from ethnic segregation. Such trends harm the social cohabitation of diverse groups of citizens, and as reported in the press, riots and social uprisings occur regularly in French banlieues and US ghettos. In Barcelona, however, has the cohabitation of immigrant groups from diverse countries created conditions for similar segregation?

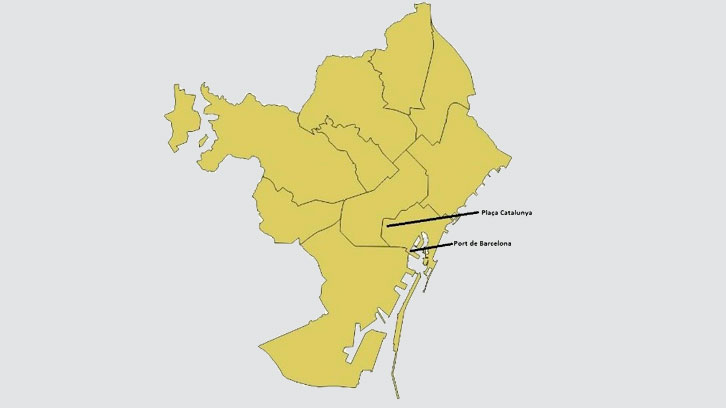

We address that question by performing a quantitative empirical analysis of a data series spanning from 1947 to 2011 purporting the demographic compositions of the various districts in Barcelona over time. Our core purpose is to test whether Barcelona’s urban structure and urban transport infrastructure, which favor mobility across different points in the city, have been tools for social cohesion and, in turn, deterring the rise of ethnic enclaves. The rationale for that trend is largely intuitive. Briefly, segregation is likely to become consolidated in a city, because the real estate market fixes the limits of accessibility to accommodations in accordance with each individual’s income. Under those circumstances, rents and the costs of housing properties are mostly determined by the distance of the dwellings to certain points of interest, especially the central business district (CDB), near to which residents prefer to settle. However, those dynamics can be upset, or at least tempered, by the existence of an efficient public urban transport network that guarantees to all citizens easy access to the CBD from different urban locations. With such a network in place, ethnic ghettos are less likely to become consolidated in cities.

Our analysis of Barcelona in that light identifies its CBD as Plaça Catalunya but not as the Port of Barcelona, for historical reasons. Our empirical exercise disentangles the existence of a self-reinforcing tendency for segregation in the city in recent decades, associated mostly with residents’ skill levels and income levels, not their ethnicity. As a consequence, gentrification has occurred in some neighborhoods; low-income citizens, mostly illiterate or unskilled, experience an important reduction in the pool of affordable real estate options that forces them to cluster in specific units of urban space, or districts. To the same extent, high-income and high-skilled residents enjoy access to exclusive residential areas not at all accessible to low-income persons. Thus, public policies are needed that can upend those self-reinforcing dynamics in order to prevent the consolidation of income-based segregation. Among potential ideas, equal education opportunities could enable access to skilled, high-paying jobs. In the same way, other public initiatives at the district level could stimulate the entry of all groups of residents into the job market as well.

Miquel-Àngel Garcia Lopez, Rosella Nicolini and José Luis Roig Sabaté

Department of Applied Economics.

Applied Economics Area.

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB).

References

Garcia–Lopez, M.À, Nicolini, R., Roig, JL. (2020). Segregation and urban spatial structure in Barcelona. Papers in Regional Science; 99(3), 749-772. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12484